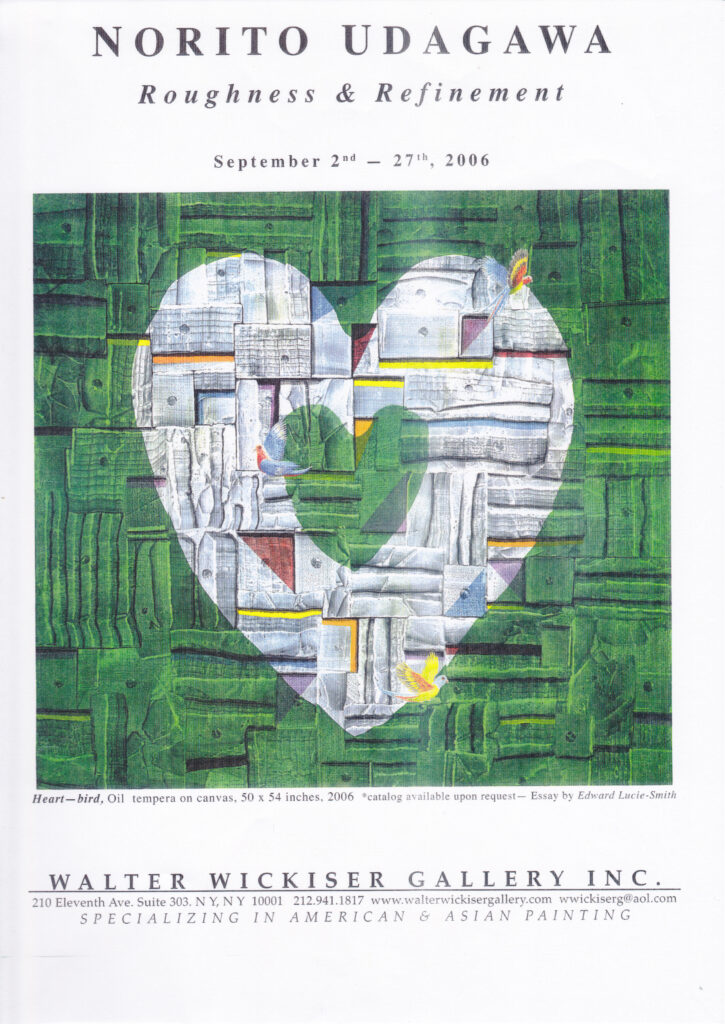

NORITO UDAGAWA | Roughness & Refinement

Norito Udagawa’s highly original work arrives at a time when westerners are once again beginning to debate aesthetic issues and preconceptions that are in many respects very different from their own. In its combination of deliberate roughness and gentle refinement it embodies ideas that are fundamental to the traditional arts of Japan, but does so in forms that are recognizably linked to the Modern Movement. In doing so it follows a path that comes almost full circle to the actual inception of Modernism.

The discovery of Japanese art by the Impressionists and their immediate successors is now generally acknowledged as one of the major liberating forces that led to the creation of a new sensibility in Europe. Europeans and Americans, however, took some time to absorb the fundamental values that formed the core of the Japanese sensibility – particularly the idea that true beauty was in essence both imperfect and incomplete. This aesthetic stance is part of the Japanese inheritance from Mahayana Buddhism.

Related to this, but sometimes in conflict with it, is the Japanese concept of ‘iki’, which inspires much of Japan’s urban culture at the present day. ‘Iki’ brings together values that are at first sight contradictory. The word suggests that things have aesthetic value because they are simple, straightforward and have the air of being improvised. It implies both calm unselfconsciousness and a spontaneous audacity. While it cannot be applied directly to nature and natural things, it can be used to describe human reactions to nature. However, these reactions cannot be deliberately cultivated, or acquired through an act of will. They are something intrinsic to the human spirit.

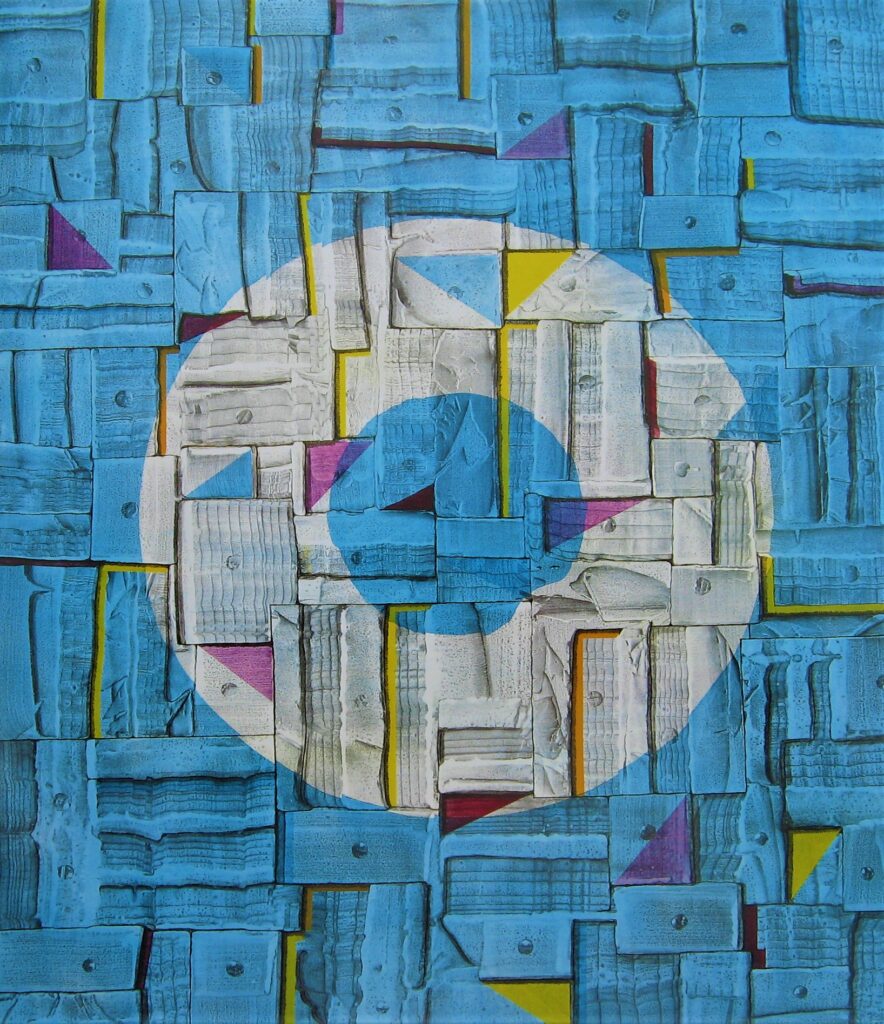

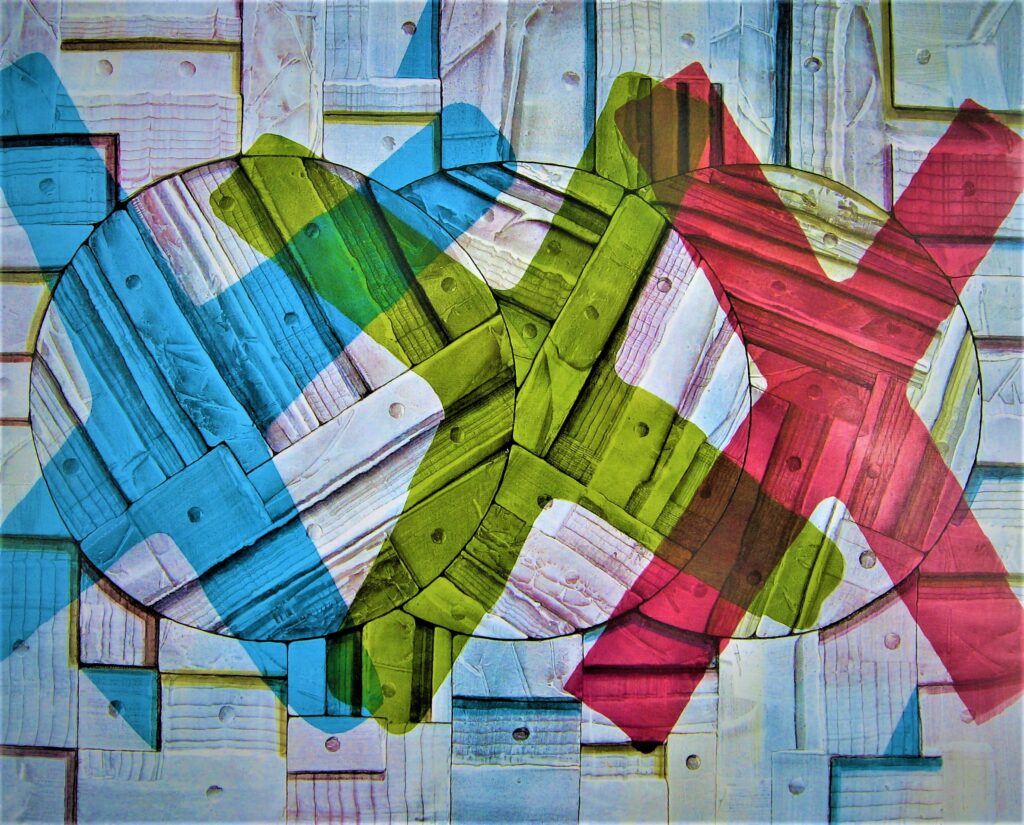

Udagawa says that his inspiration comes from the patterns in wood grain, and that this in turn relates the experiences he had as a child, when living in the Japanese countryside, and watching the light creeping through gaps in the rough wooden walls that enclosed the room where he slept. In fact, the grounds he uses for his paintings are like an extremely elaborate trompe I’oeil representation of just such a wall, created by a technique the artist likens to traditional western methods of marbling. Over these grounds he puts both boldly drawn abstract markings in transparent paint, which allow the wood grain patterns beneath to show themselves quite clearly, and sometimes also, in addition to these, finely drawn figurative images, such as the small exotic birds that appear in his painting : Heart-bird’.

The result is a seductive combination of apparently incompatible genres. On the one hand, his procedures hark to Leonardo da Vinci’s celebrated recommendation that the artist take inspiration from the random markings to be found on a wall. On another hand, there is a relationship to the painting of contemporary American abstractionist such as sean Scully, whose paintings often look as if they are derived from vernacular architecture – an impression reinforced by the fact that Scully makes and exhibits photographs of buildings of this type. And on yet another hand there are references to Pop art – the hear in ‘Heart-bird’ inevitably reminds one of Jim Dine’s use of this image.

Despite all this Udagawa’s work remains quintessentially Japanese in its commitment to freshness and spontaneity.

Edward Lucie-Smith

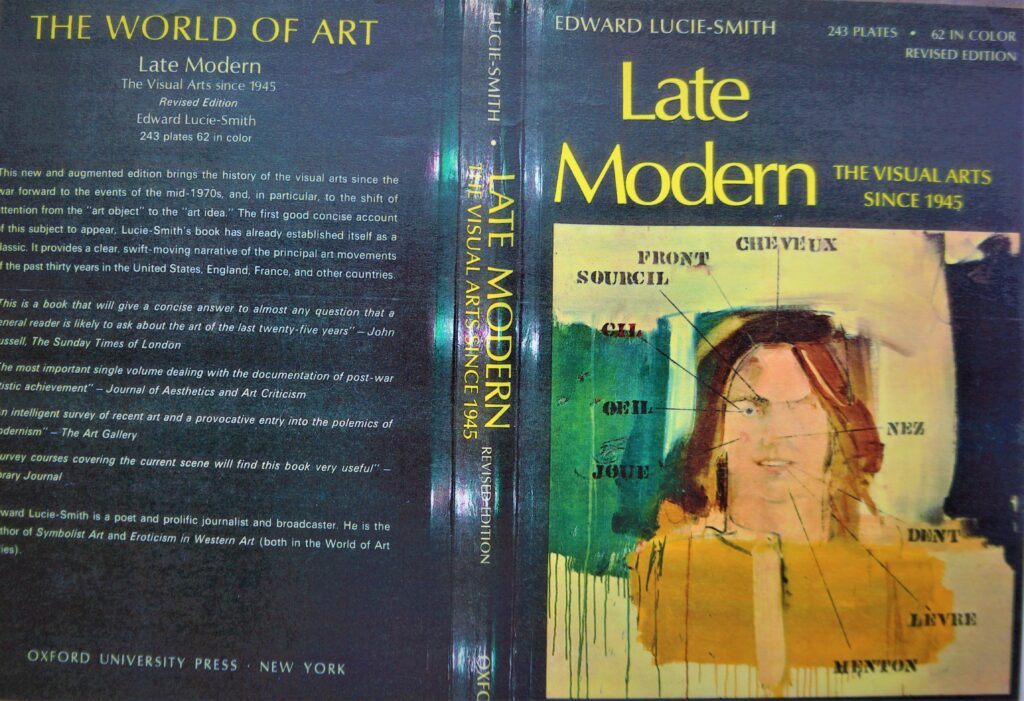

Edward Lucie-Smith is best known as a writer of books on contemporary art.

His titles include Movements in Art Since 1945, Art Today and Art Tomorrow.

His is also an exhibition curator, poet and internationally exhibited photographer.

ウォルター・ウィッキサー画廊における個展図録のエッセイ

-エドワード・ルーシー=スミス(ニューヨーク、2006年9月)-

粗さと精錬 - 宇田川宣人

西洋人が、もう一度、彼ら自身のものと多くの点で非常に異なる美的な問題と先入観を討議し始めている今、時を同じくして、宇田川宣人の非常に独創的な作品が届く。熟慮された粗さとやさしい優雅さとの結合、それは日本の伝統的芸術の根本となる考えを具現化しているが、しかし現代美術の運動に粉れもなく結ばれる形をなしている。その際、モダニズムの実際の初めへ、ほぼ一周してきた経路に沿って進む。

印象派の人と彼らと近い後継者による日本の芸術の発見は、ヨーロッパに新しい感性の創造を導いた大きな解放の影響力の一つとして現在一般的に認められている。

欧米人は、しかしながら、日本の感性の核が形づくられた根本的な価値観を吸収するためにかなりの時間がかかった。-特に真の美が本質的に不完全で不十分の中にあるという観念に。

この美的な立場は大乗仏教からの日本の遺産の一部であるが、これと関連して、しかし、時々それと対立する。今日の日本の都会文化に多くの霊感を与えている『粋』という日本の概念がある。

『粋』は、一見矛盾する価値観をまとめる。その言葉は簡素で率直で、即興的なニュアンスを含んでいるので、美的な価値観を持つことを示唆する。それは自意識を取り去った穏やかさと自然な大胆さを暗示する。

その言葉は自然や自然物質に直接に適用できるものではないけれども、自然に対する人間的反応を述べるのに使うことができる。しかし、これらの反応は、意識的に洗練することはできないし、また、意志の行為を通して身につけることもできない。それらは人間の心に内在するあるものである。

宇田川は云う。霊感は木目模様からくると。

そして、日本の田園地方に住んでいた眠った部屋をとり囲む凸凹の板壁の破れ目から光線が這うように進んでいくのを見た時の子供の頃の体験を順を追って関連させる。

実際、画家が大理石模様を表現するための伝統的な西洋画法(マーブリング)と同じような技法によって作られる彼の絵に使う下地は、まさに本当の板壁のような大変精巧なトロンプルイユ表現のようである。

彼は下地の上に、双方ともに描き込む。それらの下にはっきりと明らかにわかる木目模様が認められる透朋な絵の具で抽象的な模様を大胆に、また、それに、時々、これらに加えて、例えば彼の絵「ハート=バード」の中に現れる小さなエキゾティックな鳥のような象徴的なイメージを繊細に。

その結果は、明らかに矛盾する様式の魅惑的な結合である。

一方、彼の手順は、レオナルド・ダ・ビンチの有名な推奨、画家は壁の上に見た無作為の模様から霊感を得る、に戻り、それを傾聴する。

もう一方、あたかも自国の建築に由来したかのようによく見る絵、シーン・スカリーのような現代アメリカの抽象主義者の絵画との関連がある。-スカリーがこのタイプの建物の写真を制作して、展示するという事実によって印象は補充される。

そして、さらにもう一方、ポップアートヘの言及がある。「ハート=バード」のハートが必然的にこのイメージを用いたジム・ダインの一つを思い起させる中で。

このようなことにも関わらず、宇田川の作品は、新鮮さと自発性へのその関与により典型的に日本のままである。

エドワート・ルーシー=スミス

エドワード・ルーシー=スミスは、現代美術に関する本の著者として最も有名です。

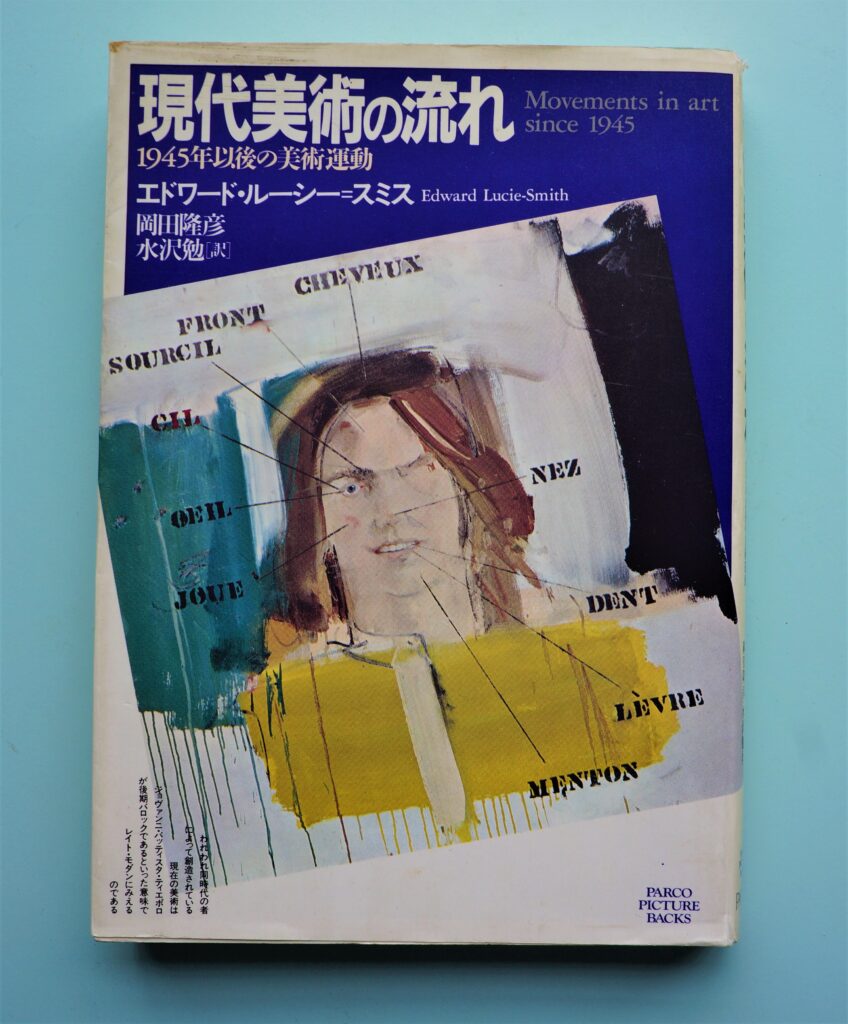

彼のタイトルは、「現代美術の流れ-1945年以後の美術運動」を含みます。

彼は、また学芸員、詩人、国際的な写真家でもあります。

(和訳:デール・スティール)

オックスフォード大学出版 ニューヨーク

岡田隆彦 水沢勉 訳 PARCO出版